The outcome of the Johnny Depp defamation trial turned a bit of celebrity jurisprudence on its head — the long-standing conventional wisdom that it’s easier for a VIP to prevail with a libel claim in the United Kingdom than in the United States.

International News 116

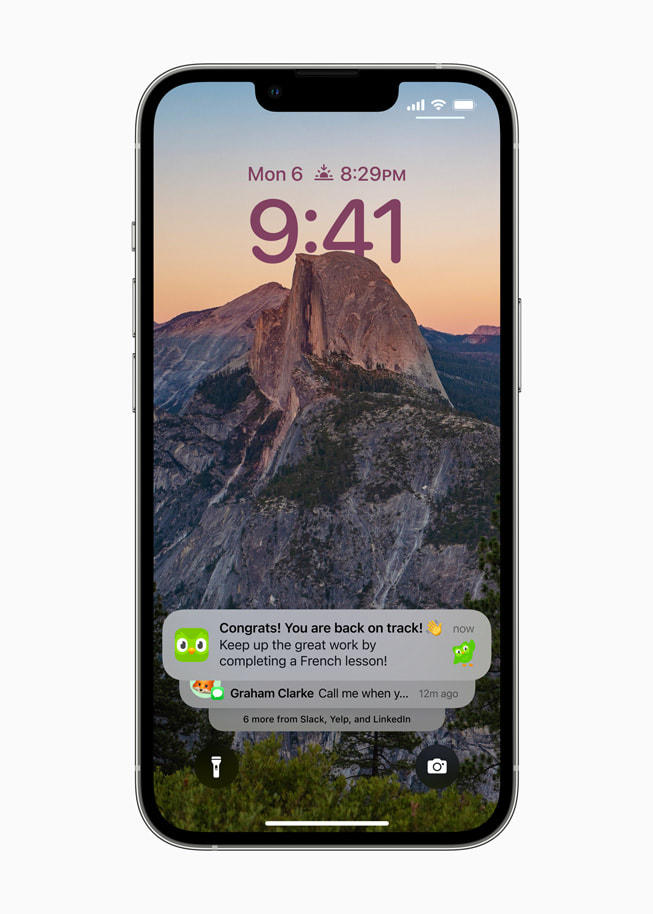

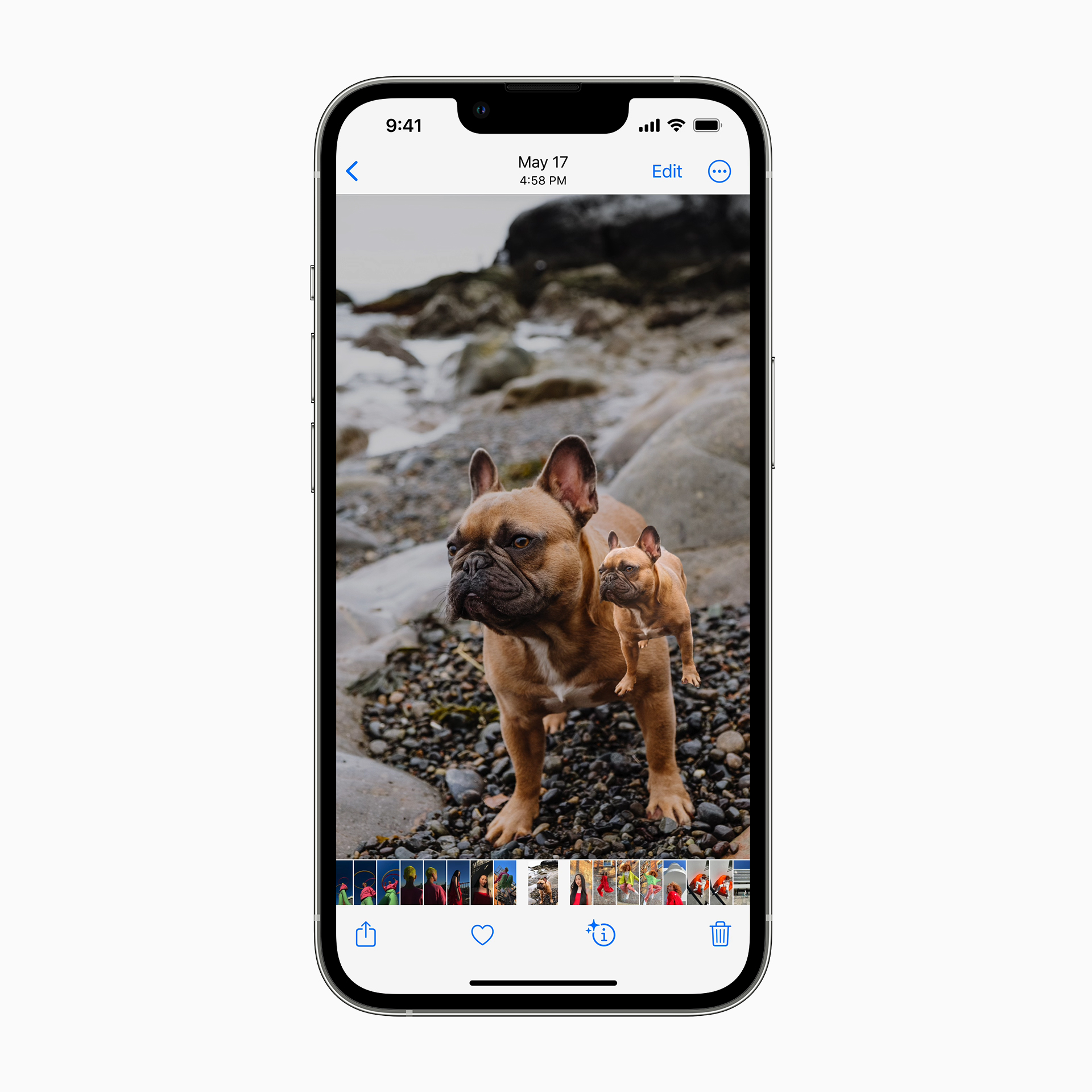

Apple unveils an all-new Lock Screen experience and new ways to share and communicate in iOS 16

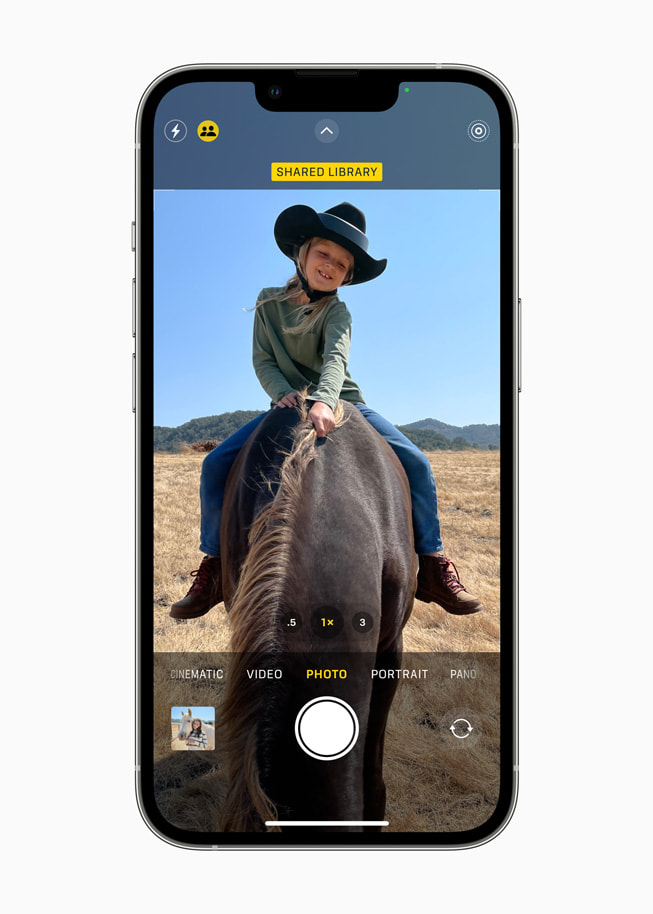

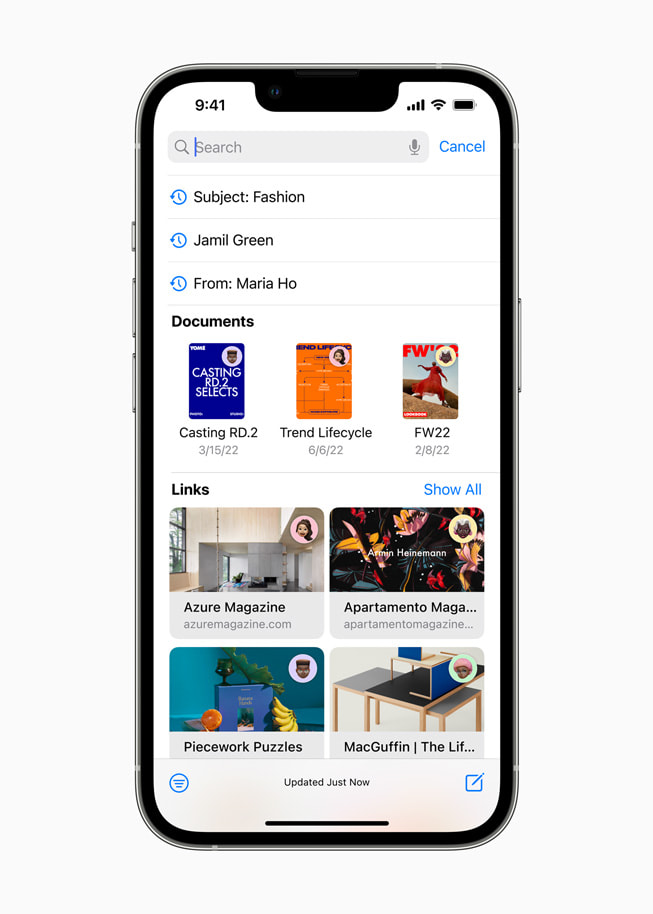

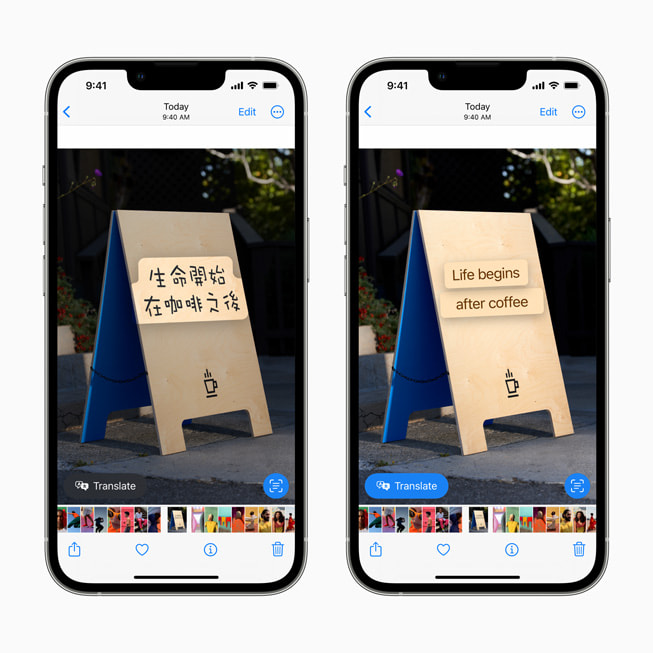

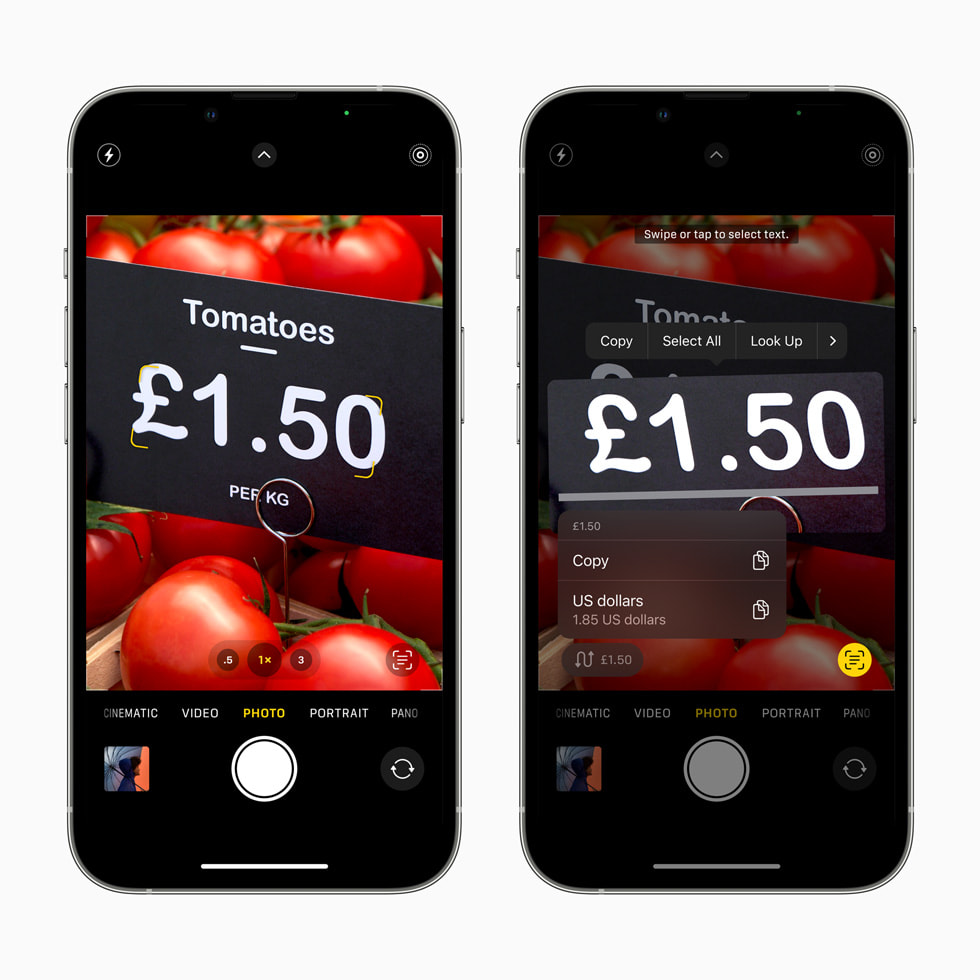

Apple Users can personalize their Lock Screen, keep family photos in iCloud Shared Photo Library, recall sent messages, schedule mail, and discover more with Live Text and Visual Look Up

A Personalized Lock Screen Experience for Apple Users

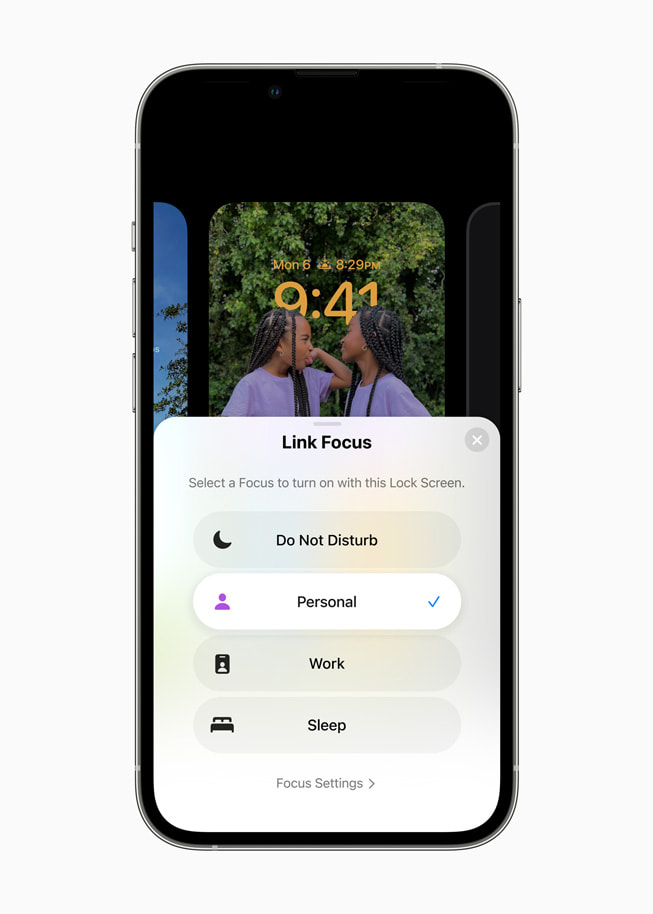

Apple Users can Find Balance with Focus

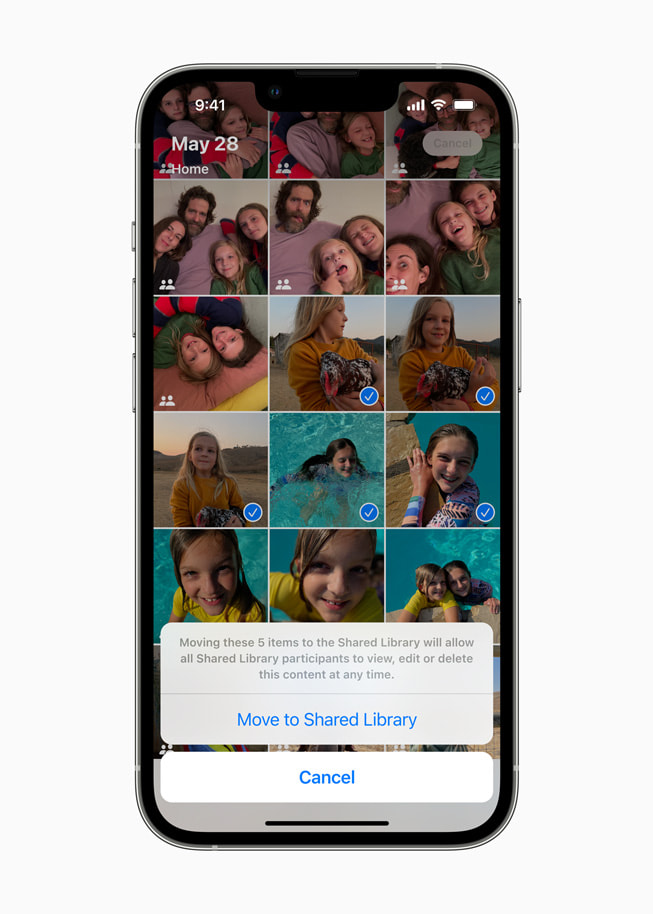

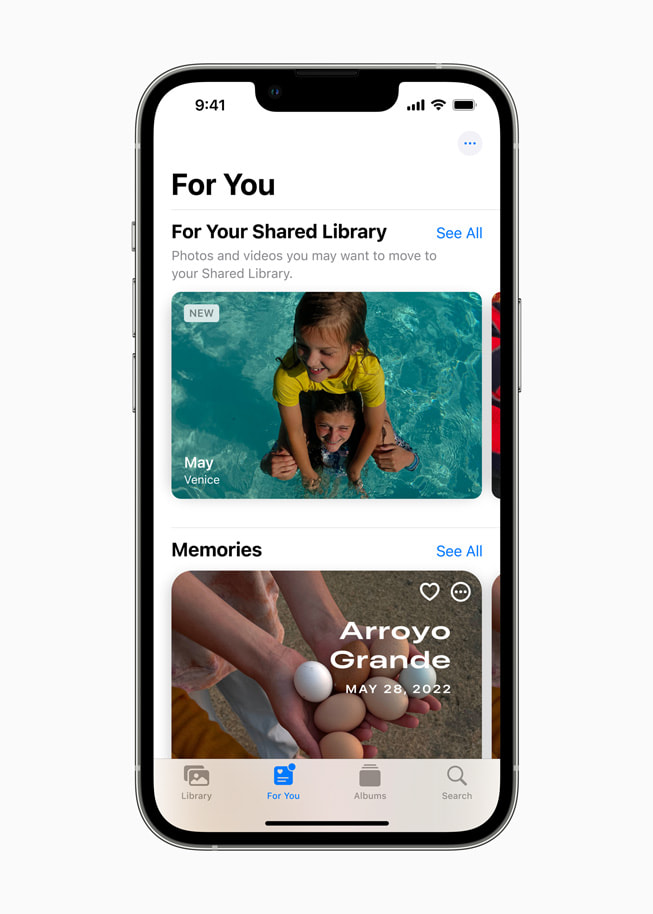

One Place for Family Photos with iCloud Shared Photo Library

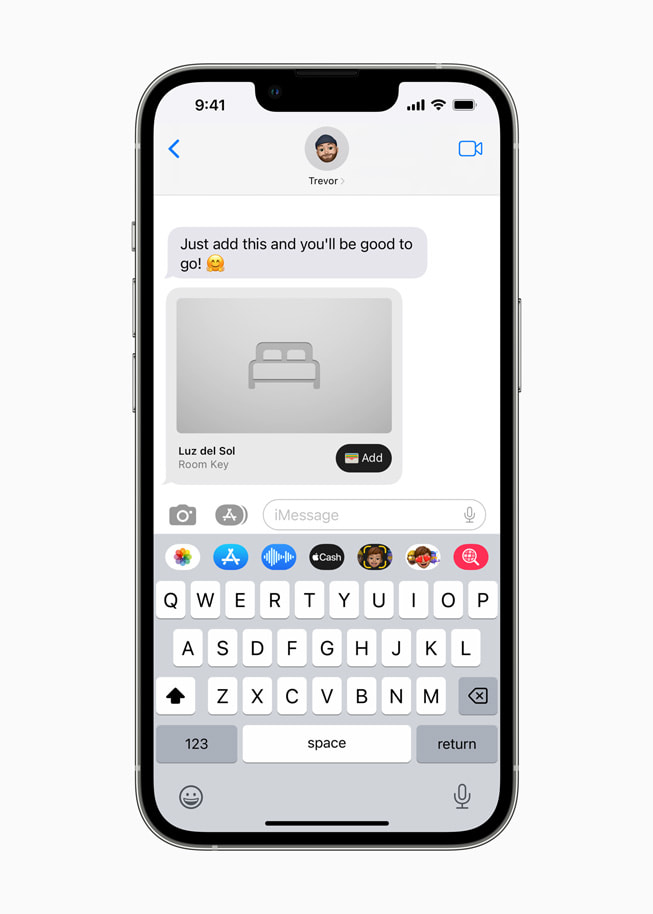

Updates to Messages

New Tools for Mail

Live Text and Visual Look Up Enhancements

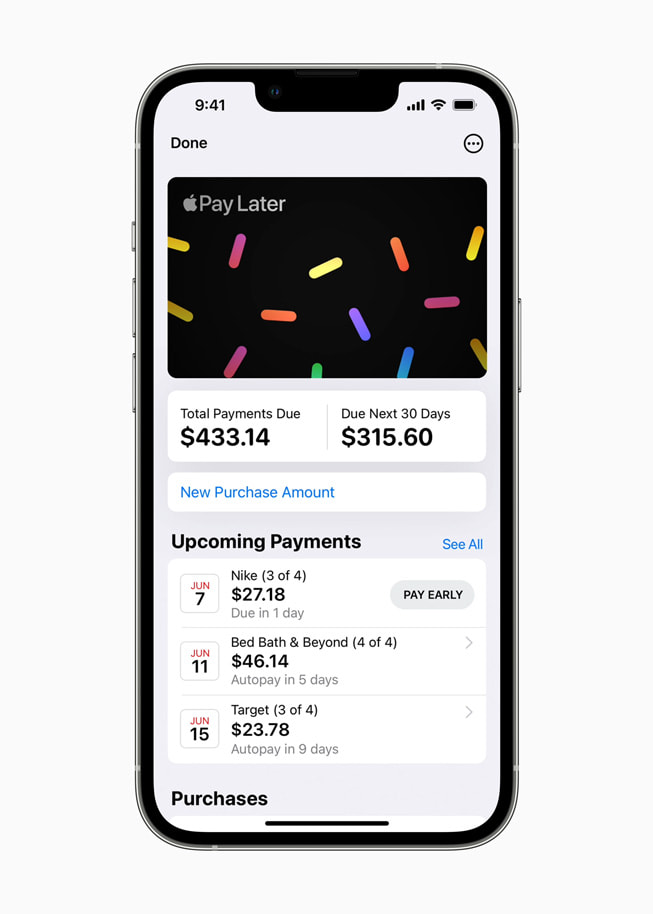

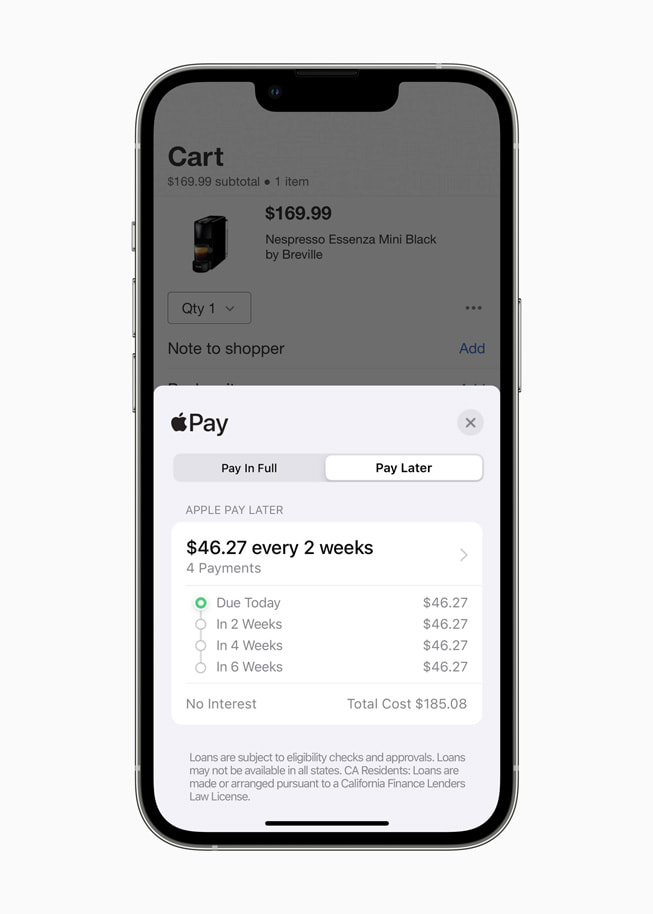

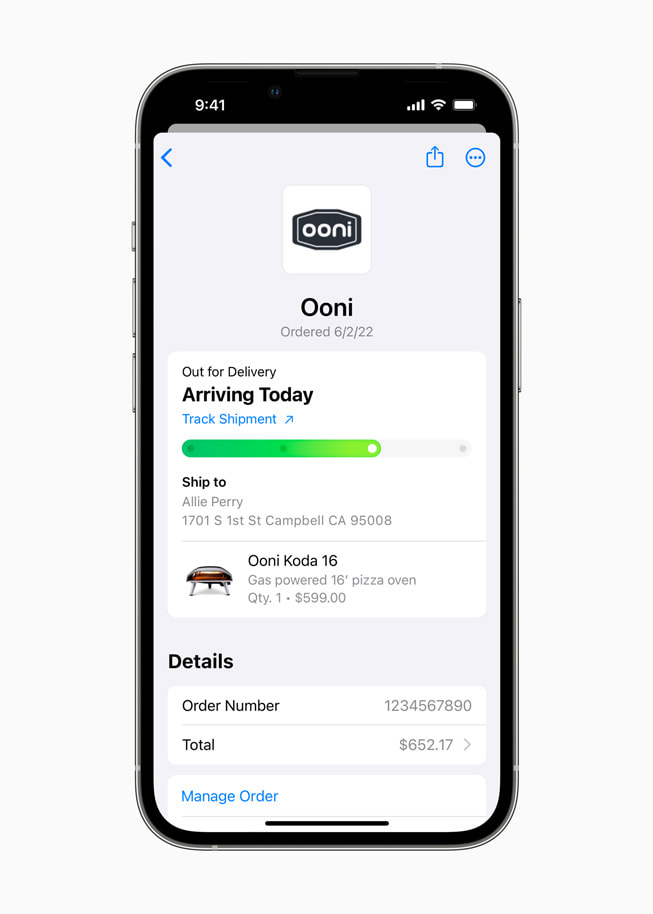

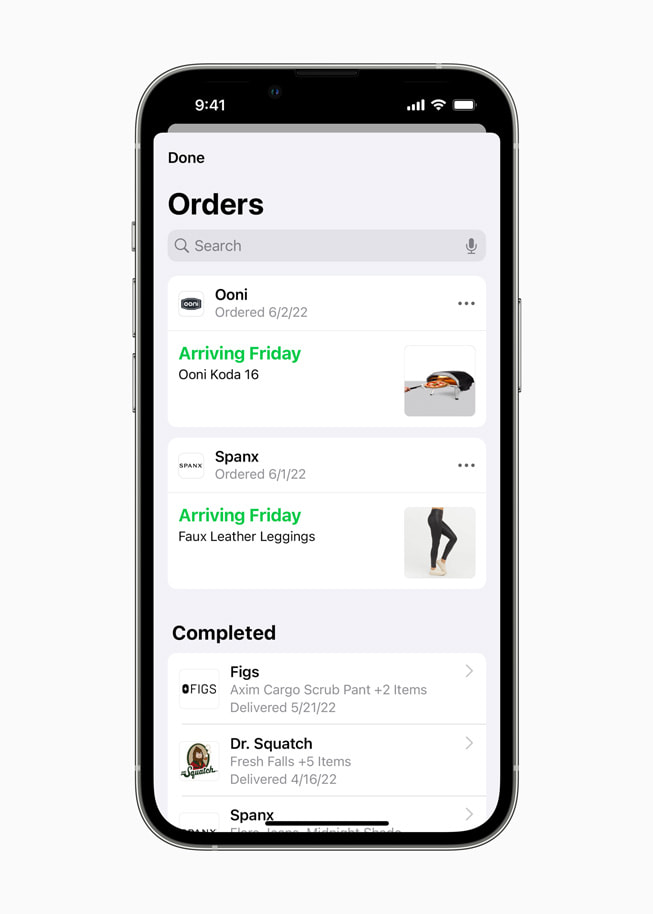

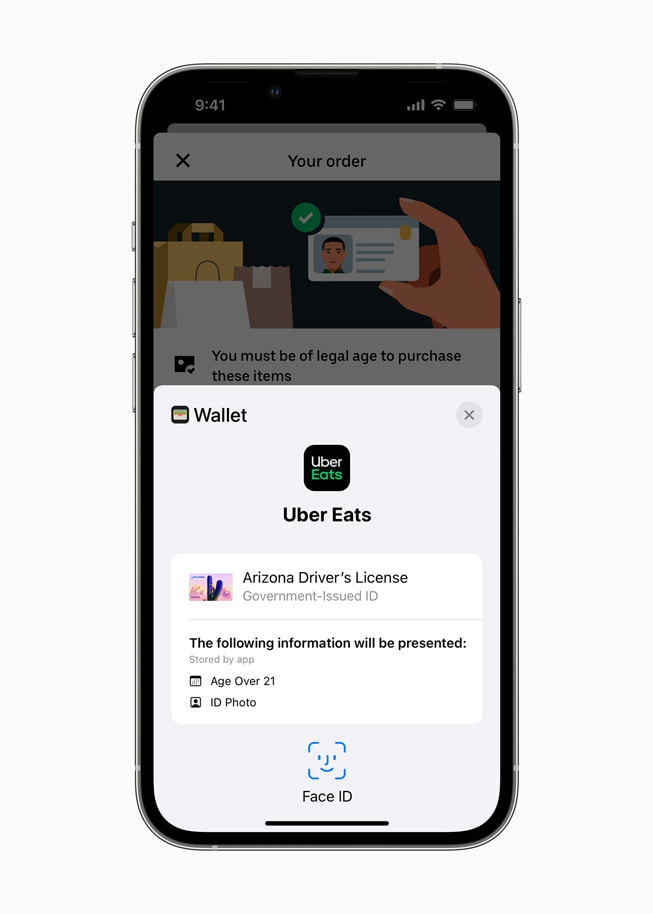

Wallet Adds Apple Pay Later, Order Tracking, and Other Features

The Next Generation of CarPlay

Additional Features

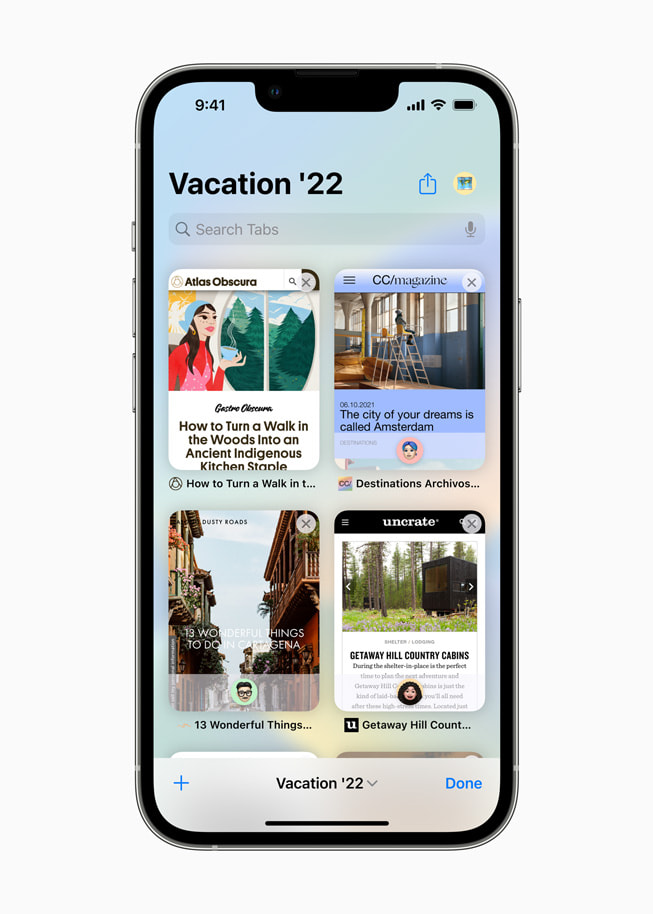

- Safari adds shared Tab Groups to share a collection of websites with friends and family, making it seamless to add tabs and see what others are viewing. Browsing in Safari is even safer with passkeys, unique digital keys that are easy to use, more secure, never stored on a web server, and stay on device so hackers can’t steal them in a data breach or trick users into sharing them. Designed to replace passwords, passkeys use Touch ID or Face ID for biometric verification, and iCloud Keychain to sync across iPhone, iPad, Mac, and Apple TV with end-to-end encryption. They will also work across apps and the web, and users can sign in to websites or an app on non-Apple devices using just their iPhone.

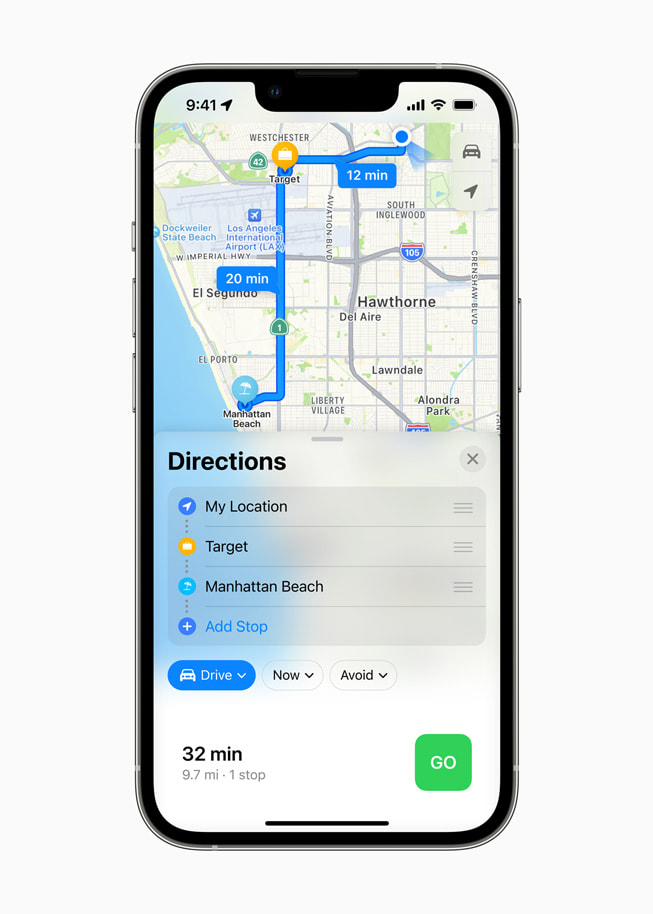

- Apple Maps is introducing multistop routing, so users can plan up to 15 stops in advance and automatically sync routes from Mac to iPhone when they’re ready to go. Maps is also bringing transit updates to users, making it easy for riders to view how much their journey will cost, add transit cards to Wallet, see low balances, and replenish transit cards, all without leaving Maps.

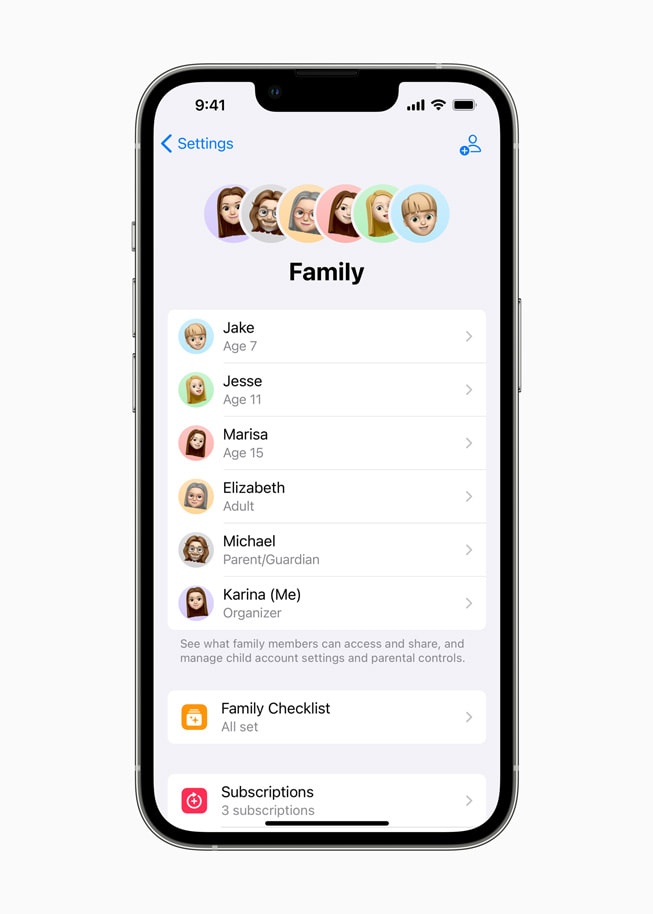

- Family Sharing offers an easier way to set up an account for a child with the right parental controls in place from the start. It includes suggestions for age-appropriate restrictions for apps, movies, books, music, and more, and a simpler process for setting up a new device that applies existing parental controls automatically. When a child asks for more screen time, guardians can approve or decline right in Messages.

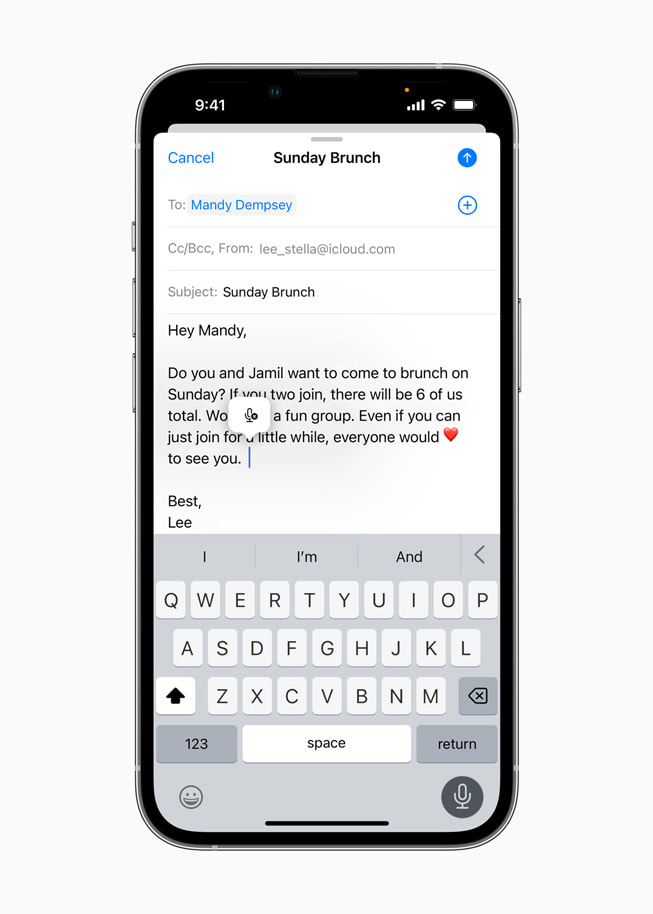

- Dictation offers a new on-device experience that allows users to fluidly move between voice and touch. Users can type with the keyboard, tap in the text field, move the cursor, and insert QuickType suggestions, all without needing to stop Dictation. In addition, Dictation features automatic punctuation and emoji dictation.

- Siri adds the ability to run shortcuts as soon as an app is downloaded without requiring upfront setup. Users can add emoji when sending a message, choose to send messages automatically — skipping the confirmation step — and hang up phone and FaceTime calls completely hands-free by simply saying “Hey Siri, hang up.”

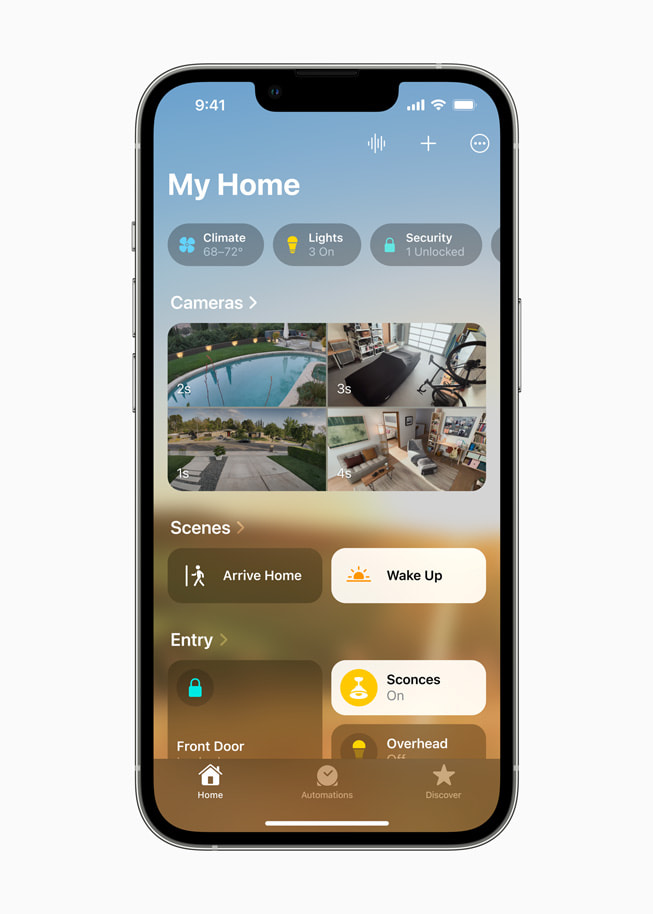

- The Home app makes it easier for users to navigate, organize, and view their accessories, and enhancements to the underlying architecture offer users more efficient and reliable control of their smart home. A software update to iOS 16 will bring support for the Matter smart home connectivity standard once it becomes available later this fall, enabling a wide variety of accessories to work together seamlessly across platforms, helping fulfill the true vision of a smart home.

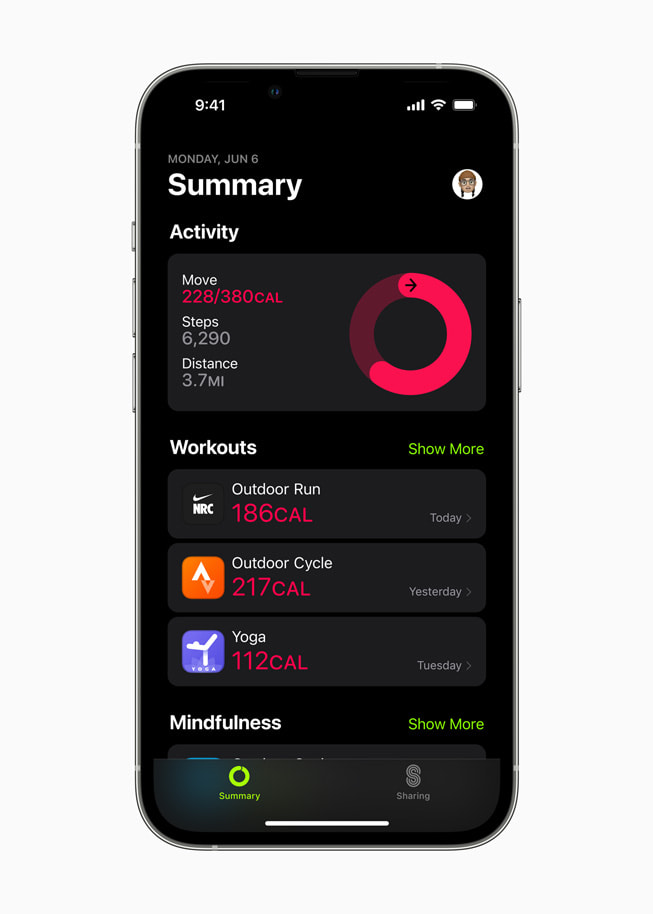

- The Fitness app is available to all iPhone users to help track and meet fitness goals, even if they don’t have an Apple Watch. iPhone users can set up a daily Move goal in the Fitness app and see how their active calories will help close their Move ring. iPhone motion sensors can track steps, distance, flights climbed, and workouts from third-party apps, which can be converted into an estimation of active calories to contribute to users’ daily Move goal. Users can also share their Move ring with friends for additional motivation.

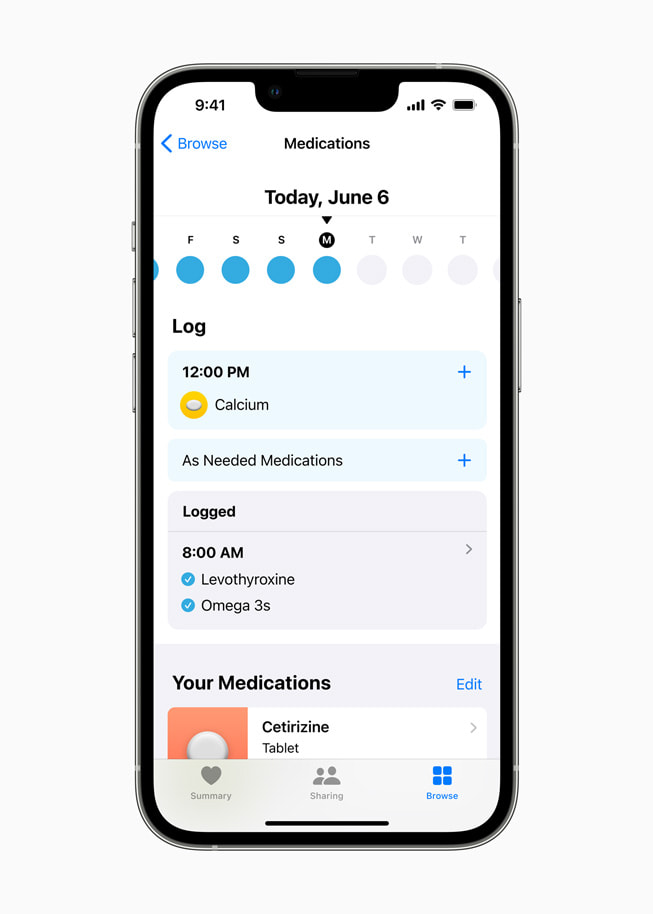

- The Health app adds Medications, allowing users to conveniently build and manage a medications list, create schedules and reminders, and track their medications, vitamins, or supplements. In the US, users can simply point their iPhone camera at a label to add a medication, read about the medications they’re taking, and receive an alert if there are potential critical interactions for their medications.5 In addition, users can share their Health data with loved ones, and easily create a PDF of available health records from connected health institutions, right from the Health app.6

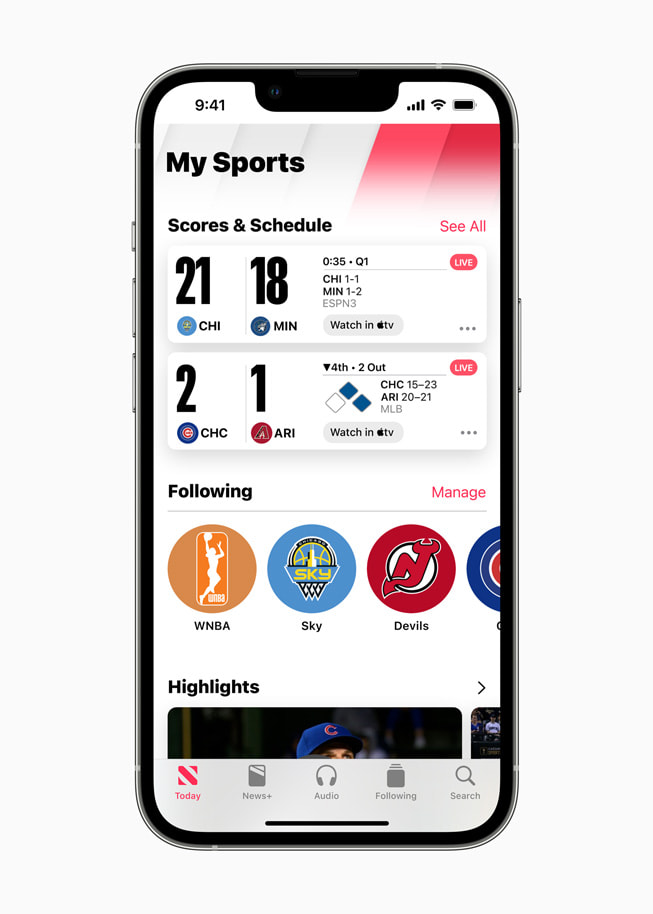

- Apple News introduces a new My Sports section to easily follow favorite teams and leagues; receive stories from hundreds of top publishers; access scores, schedules, and standings for the top professional and college leagues; and watch highlights right in the News app.

- Game Center features a redesigned dashboard that shows friends’ activity and accomplishments from games in one place, making it easy for players to jump in to play with or compete against their friends.

- Personalized Spatial Audio enables an even more precise and immersive listening experience. Listeners can use the TrueDepth camera on iPhone to create a personal profile for Spatial Audio that delivers a listening experience tuned just for them.

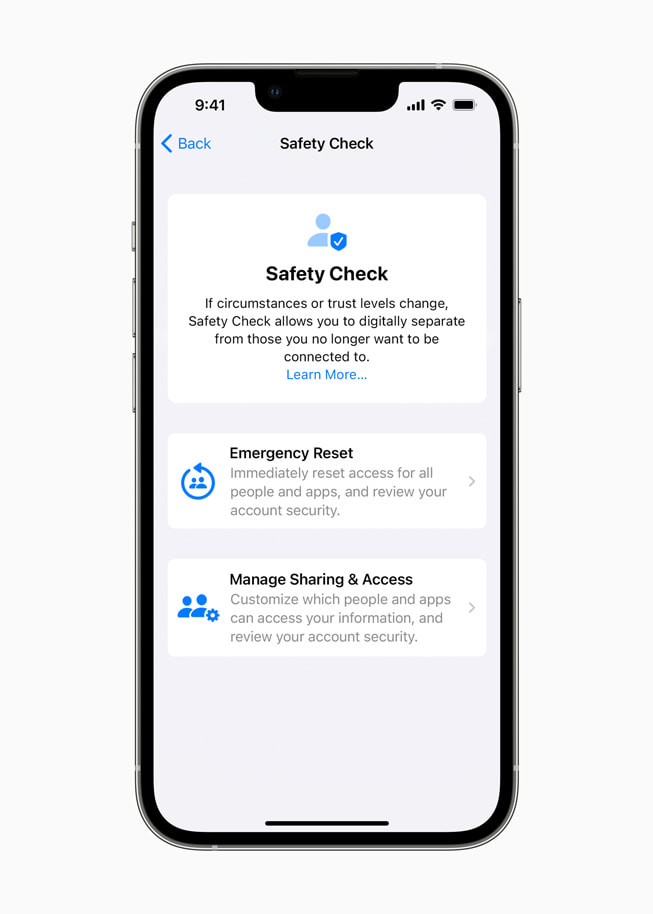

- A new privacy tool called Safety Check can be helpful to users whose personal safety is at risk from domestic or intimate partner violence by quickly removing all access they’ve granted to others. It includes an emergency reset that helps users easily sign out of iCloud on all their other devices, reset privacy permissions, and limit messaging to just the device in their hand. It also helps users understand and manage which people and apps they’ve given access to.

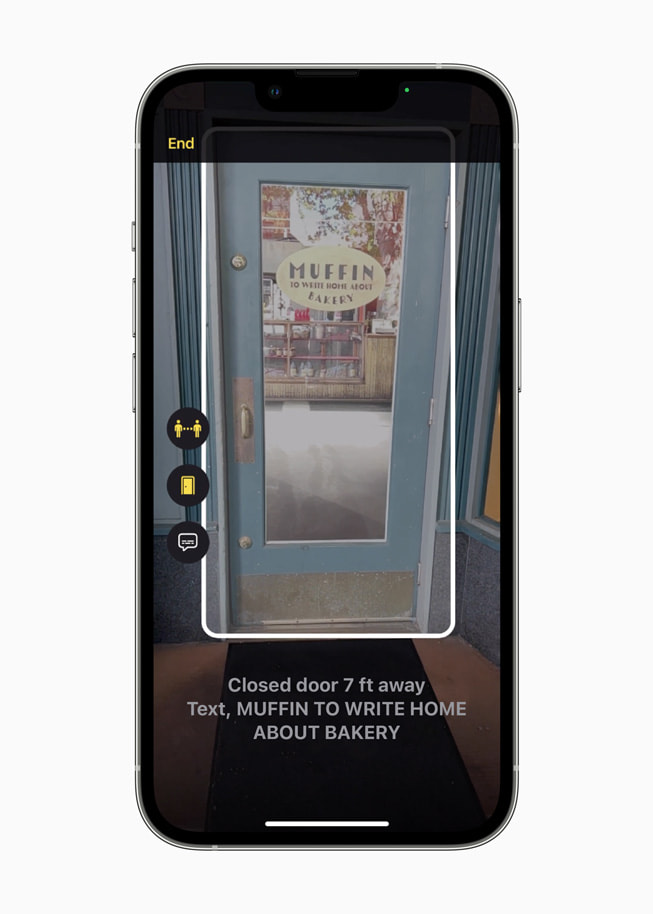

- Accessibility updates include Door Detection, which helps users who are blind or low vision to use their iPhone to navigate the last few feet to their destination, and Apple Watch Mirroring for users with physical and motor disabilities who may rely on assistive features like Voice Control and Switch Control to fully control Apple Watch from their iPhone.7 Additionally, Live Captions make it easier for the Deaf and hard of hearing community to follow along while on a phone or FaceTime call, using a videoconference or social media app, streaming media content, or having a conversation with someone next to them.8

Johnny Depp: Ready to Return to the Pirates of the Caribbean Franchise?

On Wednesday, Hollywood was stunned by the news that Johnny Depp won his defamation against Amber Heard.

Defamation cases are notoriously difficult to win in American courtrooms, and the odds seemed to be in Heard’s favour.

Depp sued Heard for $50 million in connection with a 2018 essay she wrote for The Washington Post in which she identified herself as a victim of abuse.

Depp’s legal team had to prove that Heard lied, that she did so with malice, and that said lies did long-term damage to Depp’s career.

They also had to clear the additional hurdle of proving that the article was about Depp, as Heard never mentioned him by name.

Much of Team Depp’s argument hinged on the income that he allegedly lost as a result of the Post essay.

The biggest chunk of those losses was the $22.5 million that Depp was set to receive for his work on a sixth installment of the lucrative Pirates of the Caribbean franchise, which was eventually scrapped

Depp might never see that type of payday again, his lawyers argued, and it was all because of Amber Heard.

Depp might never see that type of payday again, his lawyers argued, and it was all because of Amber Heard.

But now that Depp has been so publicly vindicated, could a long-awaited return voyage aboard the Black Pearl be in the offing?

Shortly after the verdict was announced, Depp issued a statement in which he thanked the jury for giving him “[his] life back” and promised fans that the “best is yet to come.”

And indeed, it seems that a former Disney exec — who spoke with People magazine on condition of anonymity– agrees with Depp that the future of his career looks very bright indeed.

“I absolutely believe post-verdict that Pirates is primed for rebooting with Johnny as Capt. Jack back on board,” the former exec tells People.

“There is just too much potential box-office treasure for a beloved character deeply embedded in the Disney culture.”

“With [producer] Jerry Bruckheimer riding high on the massive success of Tom Cruise in Top Gun: Maverick, there is a huge appetite for bringing back bankable Hollywood stars in massively popular franchises,” the producer said.

Of course, Depp famously remarked that he would never return to the franchise, even if Disney “came to me with $300 million and a million alpacas.”

So his asking price will probably be considerably higher than the $22.5 million the studio was previously set to pay.

The insider noted that so-called “legacy sequels” are all the rage these days, and Disney is likely already weighing its options in terms of bringing Captain Jack Sparrow back to the big screen.

It’s also possible that Disney will decide that Depp has been so badly tarnished by the events of the past few years that he’s no longer bankable as an A-list star.

Witnesses called by Heard’s team claimed that Depp’s tardiness and lack of professionalism got him blacklisted long before Amber went public with her abuse claims.

The jury seemed to agree, as the $10 million in damages they awarded were far less than what Depp requested, which seemed to be a tacit acknowledgement of the fact that she was not the reason he lost the Pirates job.

And while Depp “won” the case (though Heard was also awarded damages, albeit a much smaller amount), there was so much bad press stemming from the trial that it’s impossible to imagine any major studio shelling out to hire either of the combatants.

Currently, Depp is in the UK, where he’s receiving fervent applause everywhere he goes.

But it’s one thing to sing the guy’s praises, and quite another to write him a 10-figure check with hopes for a return on your investment.

Why Johnny Depp lost his libel case in the U.K. but won in the U.S.

“The answer is simple,” said George Freeman, executive director of the Media Law Resource Center. “It was up to the jury.”

Depp prevailed in his three counts of defamation against his ex-wife Amber Heard and was awarded $15 million, the seven-person jury announced Wednesday. The jury also decided that Depp, through his lawyer Adam Waldman, defamed Heard on one of three counts in her countersuit. She was awarded $2 million.

Depp sued Heard in Fairfax County, Va., in 2019 for defamation over an op-ed published a few months before in The Washington Post. Heard did not name Depp in the article but wrote that she was “a public figure representing domestic abuse.”

In 2020, Depp lost a similar case in the United Kingdom in which he sued the Sun tabloid for calling him a “wife-beater.” Libel law has traditionally been more favourable to plaintiffs there, even leading to “libel tourism,” where plaintiffs sue in British courts to advantage their cause.

So it surprised some when Depp prevailed in the U.S. case, given plaintiffs here face a much higher bar for proving libel of a public figure. Under American law, a plaintiff in a libel trial has to prove that they were harmed by an entity acting with actual malice, meaning they knew a libellous statement was untrue when they made it.

Mark Stephens, an international media lawyer familiar with both cases, said Depp’s legal team in the United States ran a strategy known as DARVO — an acronym for denying, attack and reverse victim and offender — in which Depp became the victim and Heard the abuser.

“We find that DARVO works very well with juries but almost never works with judges, who are trained to look at the evidence,” Stephens said.

Although Heard was not named in the British case, she testified over several days as a witness called by the Sun. The British judge ultimately ruled that the allegations against Depp were “substantially true,” writing in a 2020 ruling that “the great majority of alleged assaults … have been proved to the civil standard.”

Even though the Virginia case had a much higher standard to cross for Depp’s team, “that didn’t impact the outcome because essentially what you have got is a jury believing evidence that a British judge did not accept, so that’s where the difference lies here. Unusually, not in the different legal frameworks.”

That might explain why Depp lost in the U.K. even though he was not required to prove the wife-beater label was false. Rather, under British law, the publication had to prove that Depp was, in fact, a wife beater.

“If Depp had filed that same case here in the U.S., he would have the burden of persuading the jury that the accusation was false,” said Lee Berlik, a Virginia-based attorney who specializes in defamation law and business litigation.

The distinction is significant because in cases where there is evidence on both sides and the jury can’t determine which party is telling the truth, the party with the burden of proof loses. “It is remarkable that a judge in the U.K. found that the Sun had proven 12 separate acts of ‘wife beating’ by Depp, but in Virginia, a jury essentially found zero acts of domestic abuse and that Ms Heard’s claims to the contrary were basically a ‘hoax,’” Berlik added.

Depp sought to have the case heard in Virginia, which has a relatively weak anti-SLAPP statute, rather than in California, where he and Heard both reside. Such statutes — the acronym is short for strategic lawsuits against public participation — provide defendants with a quick way to get meritless lawsuits dismissed. Heard sought dismissal of Depp’s suit but was unsuccessful.

The other difference between the two cases is the mayhem that took place online outside the courtroom. While the U.K. case prompted outsize media coverage, the trial in Virginia took it to another level. The trial was live-streamed, with millions tuning in and dissecting the testimony on social media. “Saturday Night Live” even lampooned it.

Although jurors were ordered not to read about the case, they weren’t sequestered.

Scientists watched a star explode in real time for the first time ever

Supernovas may be way more violent than we thought.

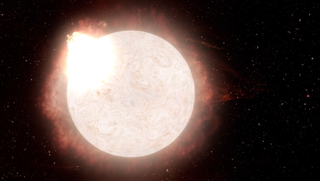

An artist’s rendition of a red supergiant star transitioning into a Type II supernova, emitting a violent eruption of radiation and gas on its dying breath before collapsing and exploding. (Image credit: W. M. Keck Observatory/Adam Makarenko)

Astronomers have watched a giant star blow up in a fiery supernova for the first time ever — and the spectacle was even more explosive than the researchers anticipated. Scientists began watching the doomed star — a red supergiant named SN 2020tlf and located about 120 million light-years from Earth — more than 100 days before its final, violent collapse, according to a new study published Jan. 6 in The Astrophysical Journal. During that lead-up, the researchers saw the star erupt with bright flashes of light as great globs of gas exploded out of the star’s surface. These pre-supernova pyrotechnics came as a big surprise, as previous observations of red supergiants about to blow their tops showed no traces of violent emissions, the researchers said.

“This is a breakthrough in our understanding of what massive stars do moments before they die,” lead study author Wynn Jacobson-Galán, a research fellow at the University of California, Berkeley said in a statement. “For the first time, we watched a red supergiant star explode!”

When big stars go boom

Red supergiants are the largest stars in the universe in terms of volume, measuring hundreds or sometimes more than a thousand times the radius of the sun. (Bulky though they may be, red supergiants are not the brightest nor the most massive stars out there.)

Like our sun, these massive stars generate energy through the nuclear fusion of elements in their cores. But because they are so big, red supergiants can forge much heavier elements than the hydrogen and helium that our sun burns. As supergiants burn ever more massive elements, their cores become hotter and more pressurized. Ultimately, by the time they start fusing iron and nickel, these stars run out of energy, their cores collapse and they eject their gassy outer atmospheres into space in a violent type II supernova explosion.

Related: When will the sun explode?

Scientists have observed red supergiants before they go supernova, and they have studied the aftermath of these cosmic explosions — however, they’ve never seen the whole process play out in real time until now.

The authors of the new study began observing SN 2020tlf in the summer of 2020, when the star flickered with bright flashes of radiation that the team later interpreted as gas exploding off of the star’s surface. Using two telescopes in Hawaii — the University of Hawaii Institute for Astronomy Pan-STARRS1 telescope and the W. M. Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea — the researchers monitored the cranky star for 130 days. Finally, at the end of that period, the star went boom.

The team saw evidence of a dense cloud of gas surrounding the star at the time of its explosion — likely the same gas that the star ejected during the prior months, the researchers said. This suggests that the star started experiencing violent explosions well before its core collapsed in the fall of 2020.

“We’ve never confirmed such violent activity in a dying red supergiant star where we see it produce such a luminous emission, then collapse and combust, until now,” study co-author Raffaella Margutti, an astrophysicist at UC Berkeley, said in the statement.

These observations suggest that red supergiants undergo significant changes in their internal structures, resulting in chaotic explosions of gas in their final months before collapsing, the team concluded.

Mars Colonies Will Need Solar Power—and Nuclear Too

A new study shows how future inhabitants of the Red Planet could run on either energy source, depending on where they set up camp.

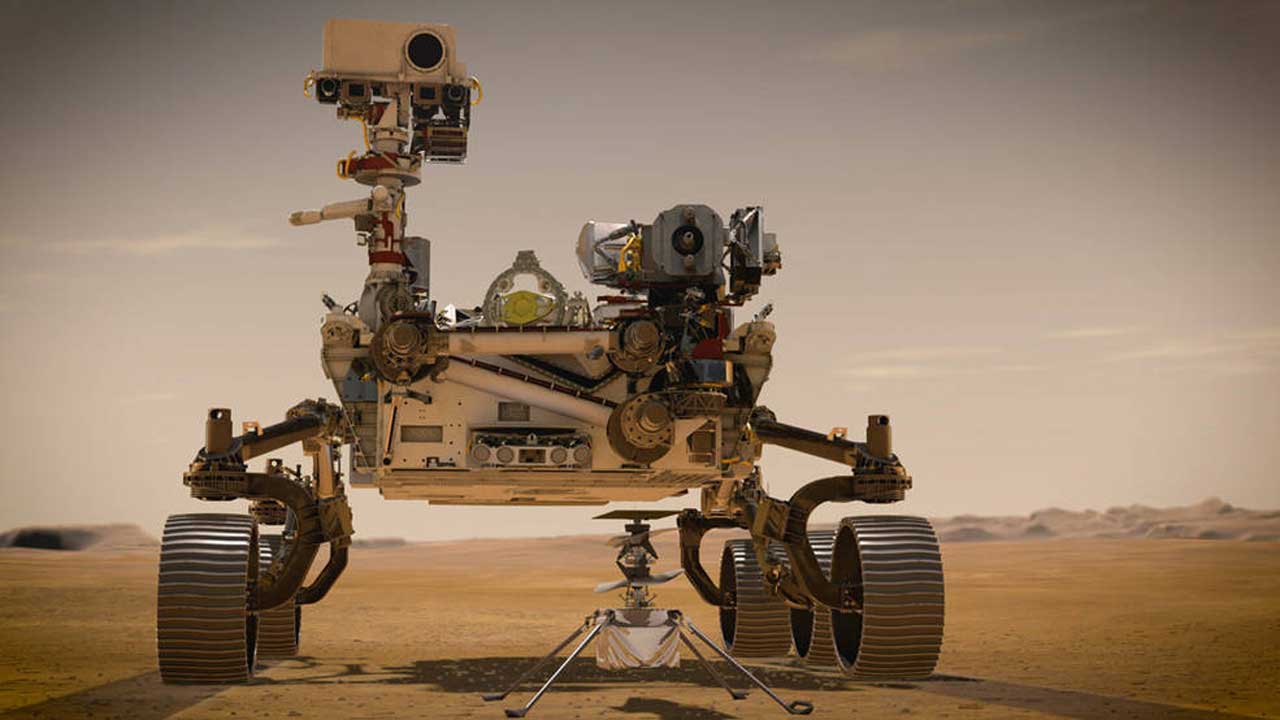

SCIENCE FICTION AUTHORS like Ray Bradbury, Kim Stanley Robinson, Andy Weir, and the creators of The Expanse have long envisioned how people might one day assemble functioning settlements on Mars. Now that NASA and the European Space Agency aim to send astronauts to the Red Planet within the next 20 years, and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk has talked about sending humans there as well, it’s time to address the practical questions involved in making those visions a reality.

One of the biggest: What’s the most practical way to power future Mars colonies? The seemingly simple question took UC Berkeley engineering students Anthony Abel and Aaron Berliner four years of hard work to figure out.

In findings published last week in Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences, they and their colleagues argue that both solar and nuclear energy sources can provide enough power for long-term crewed missions—but astronauts will face certain limitations, including how much weighty equipment they can bring from faraway Earth, how much energy solar panels can glean once there, and how well they can store energy for when it’s not so sunny. “It depends where you are on Mars,” Abel says of their results. “Near the equator, solar seems to work better. And near the poles, nuclear works better.”

The engineers based their study on the energy options for a Martian habitat built for a six-person crew. For such a remote outpost, the first astronauts would have to bring almost everything they need with them, including the photovoltaic (PV) cells, battery stacks, and nuclear reactors needed to generate enough energy for them to survive. That means these crewed missions would be shaped by how much one can bring aboard a rocket—what Abel and Berliner refer to as “carry-along mass.” “Bringing stuff from Earth to Mars is really tough, and it’s really expensive, so you want to minimize it,” Abel says.

For their study, the engineers calculated how much energy the solar or nuclear options would generate and how much carry-along mass would be needed to produce that energy. In particular, they found that over about 50 percent of the Martian surface—especially near the equator, where many of the Mars rovers and landers have alighted so far—PV solar energy outperforms other solar alternatives and requires only around 8.3 tons of carry-along mass to power a six-person habitat, thanks to advances in lightweight solar panels. (Of the three solar energy options they tried, panels with electrolysis and compressed hydrogen storage were the most efficient.) That satisfies an estimated average power demand of about 40 kilowatts, used for things like heating, lighting and rover travel, and for producing oxygen for breathing, fertilizer for crop growth, and methane for rocket fuel for the return trip.

But the weight of the needed solar equipment would go up to more than 20 tons for a Mars outpost closer to the poles. Mars is tilted on its axis by about 25 degrees, slightly more than Earth is, and its orbit is less circular, so less sunlight would reach those PV cells during parts of the year. That means nuclear power becomes more viable at the poles. The power generation equipment needed to produce that much nuclear energy would add up to about 9.5 tons of carry-along mass to produce the same 40 kilowatts of energy. That lift is doable for massive next-generation rockets like NASA’s Space Launch System and SpaceX’s Starship and Super Heavy, which can each carry payloads of at least tens of tons into deep space. (The poles also harbor ice that could provide a water source for the astronauts.)

These same kinds of trade-offs have already arisen with energy technologies used by Mars rovers. Engineers need to find the right balance between transportation weight, storage needs, and an energy system that can handle variations in the availability of sunlight. Significant sunlight reaches the surface only during the Martian day and only when dust and cloud particles don’t get in the way, says Guillem Anglada-Escudé, an astronomer at the Institute of Space Sciences in Barcelona who was not involved in the study. He’s also a member of the Sustainable Offworld Network, a collaboration of researchers, engineers, and architects studying how future colonies on Mars and other worlds might work.

Anglada-Escudé agrees with Abel and Berliner’s findings. He also believes that, if possible, one shouldn’t look at solar and nuclear energy as either/or. “Our conclusion is, you want to have both solar and nuclear,” he says. “It’s a matter of resilience. Things can fail in many different ways. The best option is to have redundancy.”

It’s also important to study solar radiance and how dust and ice affect how much light reaches the planet’s surface, and where that light can best be collected, says Daniel Vázquez Pombo, an energy engineer at the Technical University of Denmark who wrote a paper last year about a possible hybrid power system for a permanent Mars colony that includes PV arrays and storage. Maintenance for energy systems can be risky for those conducting repairs, another argument for having options.

“Do you really want to rely on a single technology? What happens if you have a systematic error or a design flaw?” Pombo says. “Diversifying is a smart idea. You don’t put all your eggs in one basket.”

The calculus may also change when it’s not just a handful of astronauts visiting for a couple months or a year but rather a permanent colony with long-term visitors, Anglada-Escudé argues. “Solar panels are a relatively simple technology, and solar gets more attractive for the very long term,” he says. “You may need more mirrors, but it will work. On Mars, finding plutonium to the quality you need for a reactor is not trivial. Solar is there, it’s safe, and we know how to do it.”

In the end, life in Mars’s rugged conditions will be tougher than anywhere on Earth. And the science and technology issues are only half the story. Settlers will have to navigate complex financial and societal issues as well, Abel says. At least when they get there, though, they’ll know how to keep the lights on.

Researchers Grew Tiny Plants in Moon Dirt Collected Decades Ago

Researchers Grew Tiny Plants in Moon Dirt Collected Decades Ago

The seedlings sprouted in the regolith scooped up in the 1960s and ’70s, but astronauts won’t be harvesting lunar spuds anytime soon.

ANNA-LISA PAUL HAD tried for years to get her hands on some real samples of lunar soil collected by Apollo-era astronauts. After she’d refined her research proposal multiple times, NASA finally granted her request in 2021, allowing her team to try growing tiny plants in moon dirt that had been lifeless for billions of years.

Her efforts paid off: Although the plants clearly struggled in the harsh, foreign material, they nonetheless managed to sprout. Paul’s team published their findings in a new study in the journal Communications Biology on Tuesday, arguing that their experiment shows that lunar astronauts could do their own greenhouse farming in a couple of decades, making them able to provide some of their own sustenance.

WANNA READ MORE SCIENCE STUFF LIKE THIS?

STAY TUNED WITH US!

Categories

- Breaking News (148)

- buisness (21)

- Entertainment (108)

- Box Office (13)

- Gaming (10)

- Marvel (MCU) (8)

- Movies (24)

- DC (DCU) (3)

- Netflix Series (2)

- Series (6)

- Enviornment (8)

- Fashion (96)

- Men's Fashion (3)

- Women's Style (3)

- Food (13)

- Health & Fitness (9)

- History (1)

- Hollywood Gossip (3)

- Home & Garden (3)

- International News (116)

- Lifehacks (21)

- Literature (30)

- Local News (75)

- Modeling (1)

- Music (8)

- Politics (10)

- Science (37)

- Psychology (2)

- Social (3)

- Sports (106)

- Technology (31)

- Traveling (70)

- Uncategorized (64)

- Vehicles (136)

Ask Your Problems

-

About Leasing

7 years ago

-

About Vehicles

7 years ago

Most commented